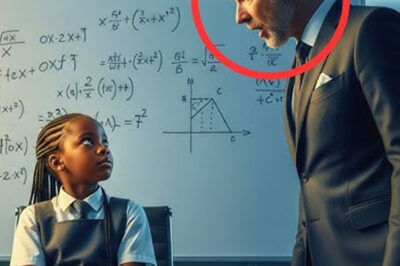

Are you telling me I’m wrong? The room

froze. You could hear the hum of the

lights. A 12-year-old black girl sat at

the front of a classroom, her braids

gently resting on her shoulders, eyes

locked on a man in a tailored suit worth

more than her family made in a year. He

was a billionaire, respected, feared,

untouchable. But in that moment, her

voice cut through the silence. Your

numbers aren’t wrong. You are. That’s

when it all began. What followed was

humiliation, denial, truth. But before

the victory, she had to face what

happens when you dare to correct power.

Brooklyn. Early morning. The wind pushed

through the chainlink fence of the

playground outside James Monroe Public

School, where Amara always waited for

the first bell. She was the first to

arrive. every single day. Sat on the

same splintered wooden bench, legs

swinging off the edge, notebooks

clutched tight against her chest. Her

school uniform was always crisp, white

shirt, gray jumper, socks pulled up just

below the knee. Her braids were always

fresh, neat rows lined with clear beads

that clicked softly when she turned her

head. Her mother made sure of it. Even

working the night shift at the hospital,

Denise never missed a morning routine.

Amara was 12 and her eyes held a kind of

quiet brilliance that most people didn’t

know how to read. She wasn’t the student

constantly raising her hand. She didn’t

need to be. She absorbed everything.

Equations, patterns, flaws, and logic.

She noticed the things others ignored.

In class, she sat in the third seat of

the second row. Her notebooks were

immaculate, her posture always straight,

but she was rarely called on. Mr.

Wittmann, the math teacher, preferred

students who spoke loudly, confidently,

especially those with last names that

showed up in donor lists or PTA

meetings. Amara had learned to keep her

observations to herself. During lunch,

she sat alone. Same corner, same tray.

She’d observe her surroundings, who sat

where, how long they stayed, how their

voices rose or fell. It was her way of

finding patterns, of understanding a

world that made little space for people

like her. Sometimes she’d come home and

tell her mom I was almost noticed today.

And they’d both laugh gently with a kind

of shared ache. Her mother, Denise, was

her anchor. Exhausted, yes, but

attentive. She pressed Amara’s uniform

every night, double-checked her

homework, redid the beads in her hair

when they loosened. Denise always said,

“You don’t have to shout to be heard.

Just make sure you’re right when you

speak. Those words lived in Amara’s

News

That’s what Whoopi Goldberg said – seconds before the studio fell into a stunned silence, and Ice Cube responded with a moment of clarity no one in the room expected.

“He’s Just a Rapper”: The Moment Ice Cube Silenced a Studio When someone dismisses a cultural icon with the phrase,…

Erika Kirk EXPOSED For CHEATING On Charlie With MULTIPLE Men in TPUSA

Erika Kirk EXPOSED For CHEATING On Charlie With MULTIPLE Men in TPUSA The “Widow’s” Game: Did Erika Kirk Orchestrate a…

DURANT CALLS OUT JOKIĆ AND DONČIĆ: Here’s How Nikola and Luka Responded at the All-Star Game

DURANT CALLS OUT JOKIĆ AND DONČIĆ: Here’s How Nikola and Luka Responded at the All-Star Game Nikola i Luka su…

HOT NEWS: Brand Collective and Reebok Go International, Flying a U.S. Star to Australia in a Statement-Making Moment

This included flying out global basketballer and two-time WNBA All-Star Angel Reese, the name behind Reebok’s latest collaborative range. Brand…

MEDIA BOMBSHELL: Is Elon Musk Preparing to Buy ABC — and Hand It to Tucker Carlson?

The media world is buzzing with a rumor that, if confirmed, could redraw the map of American broadcast news. According…

Elon Musk’s SpaceX Prepares for Starship V3 Test Flight, Advancing Vision of Deep-Space Exploration

SpaceX, the aerospace company founded by billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, is preparing for the first test flight of Starship Version 3…

End of content

No more pages to load