The bell over the diner door gave a tired jingle, and the room kept talking for exactly one more second—until it saw the jacket.

She was seven, maybe. The patrol jacket swallowed her to the knees, sleeves hiding her hands, the fabric heavy with rain and something darker. A brownish smear flaked along the left cuff, the kind that dries into memory. She didn’t make eye contact. She marched to our table like she’d practiced it in a mirror and slid a wrinkled paper across the chipped Formica.

“DADDY TO HEAVEN — NEED BRAVE MEN.”

Forks hovered. Coffee steam thinned. The jukebox clicked, thought better of it, and stayed quiet.

I’ve been called a lot of things—Cal “Sunday” Rourke, road captain for the Iron Wardens MC; veteran; screwup; the guy you want when a chain snaps at eighty. Nothing in those names prepared me for a kid wearing a man’s last day.

I read the note. Then I read it again, because reading is easier than feeling.

“What’s your name, kiddo?” I asked. My voice came out like I kept a mouthful of gravel.

“Lila,” she said. “Lila Ortiz.”

The name hit me like a backfire. Officer Daniel Ortiz had pulled me over two years earlier outside of town. I was riding hot, head full of ghosts. He saw the dog tag around my neck and the fatigue in my bones, and instead of a ticket he radioed for a ride, leaned on my bike, and said, “Find a way to sleep that doesn’t involve asphalt, Mr. Rourke.” He called me mister. He could’ve called me a lot worse.

“Where’s your mama, Lila?” I asked.

She pointed through the fogged window. A woman in a faded hoodie sat behind the wheel of a sedan that had seen too many winters. Her hands covered her face. Her shoulders shook, small and stubborn.

“She said I shouldn’t bother you,” Lila said. “She said this isn’t how the world works. But people at school said my daddy won’t get to heaven unless brave men walk him there.”

Someone behind me muttered a prayer. Men who never pray mutter prayers when a child speaks like that.

Boone, our president—rock of a man who could bench-press a pickup if you asked nice—lifted the note with fingers that could thread a needle. “Your daddy,” he said gently. “He was a police officer?”

“Yes.” She stood straighter. The jacket buckled around her like a parachute in wind. “He saved people.”

“What happened?” I asked before I could stop the question.

“Work,” she said. A single word, too big for her mouth. “Someone got sick. He… didn’t come home.”

I could’ve argued with fate. I could’ve argued with policy and training and all the talk shows that turn lives into points on a scoreboard. I could’ve said cops and bikers don’t mix except on the side of a highway with ticket books and bad attitudes. But the jacket was too big, and the cuff was still marked, and a seven-year-old had walked into a room full of leather and asked for help without blinking.

“Who told you brave men walk people to heaven?” Boone asked.

“My dad,” she said. “When he tucked me in.”

We paid our check. We walked her to the car. The woman—Marisol—rolled down the window slow. She looked at us with the kind of fear that doesn’t come from movies. I recognized it. It’s the fear of running out of strength.

“I told her not to bother anyone,” she said. “I’m sorry. I’m—”

“No ma’am,” Boone said, polite in a way you can’t teach. “There’s no bother here. We’ll come.”

Her eyes widened like we’d said a word she hadn’t heard in too long: yes.

The busboy had snapped a picture when Lila set the note down.

By the time I got to the shop to tune the bikes, the photo was on the internet, marching from one screen to the next, picking up comments like burrs. Half the town cried in the emojis.

Half warned the sky would fall if bikers and badges stood on the same patch of ground. A handful of loud accounts threatened to “show up and make some noise” at the funeral, as if grief were a show with an open mic.

“Don’t read the comments,” Gator said, rolling a tire with his knee. “Don’t feed the zoo.”

“I ain’t feeding it,” I grunted. “But if it throws something, I’m not letting it hit the kid.”

We ride for toys at Christmas, for vets with empty fridges, for kids with hair growing back after chemo.

We ride because the roar of a hundred engines makes you feel like the world’s heartbeat found its pace again. We also ride because promises are heavy and need horsepower.

I wrote a message in our group: “Escort for Officer Ortiz. The ask came from a daughter. Keep it clean, keep it quiet, keep it kind.”

By sundown, other clubs had chimed in.

The Gravel Saints, the Thunder Sisters out of the next county, even the church riders who wear crosses where we wear skulls.

My phone buzzed until the battery begged for mercy.

Not everyone promised peace.

A few warned we were “taking sides.” One handle I didn’t recognize wrote: “We’ll be there to film. Try something.” I set the phone facedown and changed the oil with more force than necessary.

Sergeant Hannah Price called me just after dark. We’d met on opposite ends of a traffic stop once. She was all square jaw and steady eyes, the type who writes a warning and says, “Please get that taillight fixed,” like please is part of the uniform.

“I hear your club plans to attend,” she said.

“Yes, ma’am.”

“I’m asking you to reconsider.”

“Respectfully, not happening.”

A pause. “If you do come, we’ll have to coordinate. There’s talk online.” Another pause, heavier. “Officer Ortiz was my friend.”

“We’ll keep our people in line,” I said. “We’re not there to pick a fight, Sergeant. We’re there to keep a promise that didn’t come from us.”

She didn’t answer right away. When she did, her voice had a thinner edge. “He died on a call in a motel off Exit 12. He used Narcan, performed compressions until the EMTs arrived. He…” She exhaled. “He did everything right. Sometimes everything isn’t enough.”

“I know,” I said. And I did.

“Tomorrow, 10 a.m.,” she said. “Riverside Chapel, then Hillcrest Cemetery. If the power cuts—the storm looks mean—there’s a generator, but I don’t trust it.”

“If the power cuts,” I said, looking at a row of headlamps bright enough to turn night into a suggestion, “we’ll handle it.”

Morning came like a bruise.

Clouds muscled in from the west.

The flags on Main Street went sharp and straight in the wind. I left early, the road empty enough to hear my thoughts, which I ignored. When I turned into the chapel lot, the first thing I saw was not a hearse but a river of chrome.

Bikes lined up in clean rows. Iron Wardens patches.

Gravel Saints.

Thunder Sisters’ pink lightning bolts. Christian Riders with their fish symbols. A handful of guys from clubs we used to snarl at from across parking lots without knowing why. Engines idled and coughed and killed in turn, seat by seat, like a choir learning a harmony.

Then the cruisers arrived. Blue striping. Powdered hats. Shoes shined to black mirrors. Hands near hips but not on holsters. Faces unreadable. The storm pressed low, waiting for sparks.

You could feel the old scripts trying to cue us. Us versus them. Loud versus lawful. The internet would’ve loved it. But the jacket belonged to a child now, and the cuff still remembered.

Sergeant Price stepped out of her unit and walked toward us slow, the way you walk toward a stray dog with a wounded paw. Boone met her halfway. I stood to his right. She looked up at him, then past him at the sea of bikes, then straight at me.

“Mr. Rourke,” she said.

“Sergeant.”

“Thank you for coming.”

It’s a small sentence, but it can move heavy things. Something in our row of shoulders dropped an inch. Something in theirs did too.

Marisol pulled in then, Lila beside her in the passenger seat, swallowed by the jacket, chin lifted.

The kids from her class had made a paper banner that read WE LOVE YOU LILA with letters of different sizes, the way love never matches. A couple of people with homemade signs lurked near the far fence, phones poised like spears. The first drops of rain smacked dust flat.

The chapel lights flickered as the preacher began.

Lila perched between her mother and a row of officers, her feet not touching the floor, jacket enormous and stubborn and hers.

The preacher said words the rain tried to drown. A deacon wheeled out the generator. It coughed, tried, failed. The lights cut. The storm took the room like a hand over a candle.

Before anyone could panic, Boone’s voice rose from the back: “We got it.”

We filed out into the dim.

We turned keys.

One by one, a hundred, then two.

Headlights leaped awake, white cones carving the water. The bikes made a corridor of light from the chapel door to the hearse, and people, even the ones with phones, put their phones down because some moments ask for hands.

Lila stood at the edge of that corridor holding the note, the paper soft and thin now like it had been folded and unfolded all night. She looked up at me. The dried smear on her cuff had softened in the rain and gone dark again, as if grief can learn new ways to be visible.

“Will they be scared of us?” she whispered.

“Who?”

“The angels.”

“Not today,” I said.

She took a step toward the hearse and then stopped.

Her lips pressed tight like she was holding back an ocean.

She turned to the row of badges and to our row of patches and to the people without any labels at all and raised her small hand.

“Excuse me,” she said, because her father had taught her to be polite. “My dad was kind. That’s all. Please remember that.”

No slogans. No debate. Just a child asking the weather to be less cruel.

We rode slow.

The road to Hillcrest had puddles that pretended to be lakes.

The procession stretched long enough to make patience a virtue.

The few folks with signs tucked them in their jackets when the wind got real; they watched instead, as if they’d come ready to perform but found themselves in an audience.

At the graveside, the preacher’s mic died for good.

The world fell to the sounds that tell the truth—boots in mud, umbrellas complaining, a woman’s breath hitching and finding its rhythm again. The police chief folded a flag with practiced hands. He spoke with no amplification, and the storm did us the courtesy of listening.

When he finished, Lila tugged on her mother’s sleeve, then looked for me.

She lifted her arms the way kids do when they want to be taller than sadness. I picked her up and felt how light seven years can be and how heavy.

“Can you say something?” she whispered. “You’re big. People listen when big men talk.”

Size has never made my words better, but the day required more than the mechanics of the moment. I stepped to the foot of the casket. I didn’t write speeches. I wasn’t about to start.

“Officer Ortiz,” I said, and my voice came out steady by accident, “was the kind of man who changed other men’s minds quietly.

He did it to me without saying much more than my name.

Today you see jackets and uniforms. You see old stories about who belongs where and who respects whom. I’m asking you to look at something smaller.”

I held up the note. “A child’s handwriting. A request that we walk her father home.”

I pulled my patch knife and slid it under the thread at the edge of my vest’s back rocker—IRON WARDENS curving like a shoulder of sky. The patch had ridden with me through three summers, two winters, and more miles than years. I set it on the casket with two fingers and a breath.

“We put our names on our backs,” I said. “Today those names are his.”

Boone followed, laying his weathered gloves next to my patch.

The Thunder Sisters placed a matte-black helmet, visor up as if to say see you.

A young cop removed the strip with his last name and set it beside the helmet like a bridge.

The police chief took the badge from his chest—a weight you earn and carry—and placed it carefully on top, rain beading and not winning.

It wasn’t planned. It didn’t need to be.

Leather and brass, cloth and metal, a pile of ordinary power turned sacrament by proximity to love.

A man I didn’t recognize stepped from the edge of the crowd. He wore a jacket too thin for the rain and a look too raw for public. He cleared his throat.

“Sergeant Price,” he said. “My brother’s the reason Officer Ortiz was at Exit 12.

He’s here today, and he’s breathing because that man didn’t give up on him. He’s embarrassed to say this himself, so I’m saying it for him.”

The brother lifted a hand from under an umbrella. People turned. The internet probably would’ve argued with him. The rain doesn’t argue with anyone.

“Thank you,” the thin man said, voice breaking. “Thank you for trying. Thank you for being the kind of officer we hope for when it’s us or someone we love.” He looked at us then—at the patches and the scars and the habit of standing with arms crossed—and nodded. “Thank you for showing up for his little girl.”

The word traveled like it had wheels: show up. Not fix. Not win. Not be right. Just be there with the weather and with each other.

When it was over, the news called it unusual and moving.

Clips of the headlight corridor slid between advertisements for things no one needed.

Someone edited our ride into slow motion over a piano track that hit all the same notes at the same time.

People who had promised to make noise posted long explanations for why they’d stayed home. The town went back to work. The storm left. The grass moved in a way that said it had learned something.

We rode back to the diner because grief makes you hungry in a hollow way. Lila sat in a booth with hot chocolate big enough to float.

The jacket was draped over the seat to dry. The cuff looked more like a memory than a stain.

Marisol held the cup for her daughter, steadied her hand, and in that gesture there was more bravery than anything I had done all day.

Sergeant Price stopped by our table. She didn’t say much. She slid a card across—her direct number—and said, “If you ever need an escort for a toy ride, call me. Traffic gets hairy on 28.”

Boone grin-smirked. “We don’t mind hairy.”

“I can tell,” she said, deadpan. Then, softer: “He would’ve liked today.”

“Then we did it right,” I said.

Ten years fit in a sentence.

You live them in oil changes and birthdays and broken ribs and late notices and new tires and inside jokes that survive winters.

You live them in the way a town slowly lets you be the thing you are instead of the thing it decided first. You live them in the space between a child’s hand and a handlebar.

On a bright morning with air sharp enough to cut apples, I stood in the shop with the doors rolled up and the radio low.

The bell over the front door jangled, and a young woman stepped in wearing an EMT trainee uniform that made me stand a little straighter.

“Mr. Rourke?” she said. There was no maybe about her age now. Seventeen has a voice that already knows what it wants.

“Just Sunday,” I said, out of habit.

She smiled in a way I recognized. “Lila works,” she said, as if she were introducing herself to her own life.

On a chain around her neck hung something small and worn—the name strip that had sat on her father’s coffin beneath a helmet and beside a patch.

She reached into her bag and set my back rocker on the counter. It had been framed in shadowbox glass, the fabric cleaned but not perfect, the edges still rough with the memory of a knife.

“I think this belongs with you now,” she said. “Mom kept it safe. She said one day I’d know when to return it.”

“You could keep it,” I said.

“I’ve got something else.” She opened her palm. A small patch from the corner of the big rocker sat there—RIDE GENTLE stitched in white, the thread a little crooked like the person who sewed it had done it late and tired and happy. “I’m taking this one with me. Sometimes the ambulance siren makes people panic. I want to walk in already slowed down.”

I slid the shadowbox off the counter and leaned it against the wall in the place we hang things that mean more than the parts they’re made of.

Then I fished in the drawer where I keep everything I can’t throw away: pennies flattened on railroad tracks, ticket stubs to games where we lost by a lot and still had a good time, a dog tag that isn’t mine but might as well be.

“Here,” I said. “He called me mister the night I didn’t deserve it. I figure I can call you what you earned.” I pressed the dog tag into her hand. “Wear it on days when the world is loud. It reminds you that some noises are just weather.”

She fastened it next to the strip. It looked right there.

“You going to ride?” I asked. “Not today. Someday.”

She looked past me at the row of bikes and beyond them at the slice of road. “Mom says eighteen,” she said. “But she also says if I’m going to do something, I’m going to do it with people who know what they’re doing.”

“She’s not wrong,” I said. “When you’re ready, we’ll make a circle in the back lot. We’ll stall it and laugh and stand it back up. We’ll talk about clutch and kindness. They’re the same skill.”

She laughed, and it was the laugh of a seven-year-old in a too-big jacket without the weight.

At the door, she turned. “You ever think about that day?” she asked. “The storm, the lights, the way everybody forgot what they were supposed to argue about?”

“I think about the note,” I said. “How brave asks simple.”

“Me too,” she said. “Sometimes people don’t need us to fix the whole world. They just need us to show up with headlights.”

She left.

The bell talked to itself and settled down.

I looked up at the rocker on the wall, at the curve of the word that had carried me through so many miles, at the place where the corner had been cut out and given away on purpose.

We’d been called a lot of things.

Some of them we’d earned.

Some of them were lazy names thrown from passing cars.

None of them mattered as much as what we did when a child walked in wearing her father’s last day.

We didn’t solve the internet.

We didn’t cure addiction.

We didn’t end the weather.

What we did was smaller and, I think, bigger. We put what we had—names, patches, lamps, time—on the line between a family and the dark.

The bell jingled again. Gator stuck his head in. “You ready?” he said. “Toy run on 28. Sergeant Price is waiting at the light to wave us through.”

“I’m ready,” I said, and I was.

We rolled out two by two, mirrors catching the noon, chrome making sense out of sun.

Out on the highway, the wind pulled at my vest, and for a second I reached back the way you reach for a habit and remembered that the heavy piece was gone, on a wall and in a frame and in a life moving forward.

The space it left filled with air and with road and with something I don’t have a name for that feels a lot like mercy.

At the red light on 28, a patrol car idled.

Sergeant Price leaned out the window and gave the smallest of salutes. The light turned green. We moved as one.

Past the diner, past the chapel, past the place where the power used to flicker. The sky was ordinary in the good way. The town breathed.

Sometimes, in a country that forgets how to listen, you take your turn making a corridor of light. You do it with what you’ve got.

Engines. Headlamps. A child’s request.

And men and women who show up—steel on the outside, soft where it counts—walking somebody’s loved one, or someone’s last bad day, toward home.

News

Tyrus emerges as a hero after dismantling Jasmine Crockett on live air: A relentless takedown left Crockett speechless and exiting the stage in humiliation.

SHOCKING MOMENT: Tyrυs Crυshes Jasmiпe Crockett oп Live TV—Stυdio Stυппed, Crockett Storms Off Stage iп Hυmiliatioп! Iп a jaw-droppiпg live…

SH0CKING LIVE TV MELTDOWN: You Won’t Believe What Happened When Jasmine Crockett Brutally Humiliated Erika Kirk by Calling Her a “T.R.U.M.P Puppet”

In the realm of live television, where emotions run high and tensions can erupt at any moment, few incidents have…

HISTORIC MILESTONE: THE CHARLIE KIRK SHOW SURPASSES 2 BILLION VIEWS. Just announced — the very first episode of The Charlie Kirk Show, featuring Megyn Kelly and Erika Kirk, has now soared past an astonishing 2 billion views worldwide. Fans are hailing it as “groundbreaking,” while industry insiders caution that “this is only the beginning.”

HISTORIC MILESTONE: THE CHARLIE KIRK SHOW SURPASSES 2 BILLION VIEWS In a moment that few could have predicted but many…

The WNBA season was a brutal battleground for Angel Reese, but a shocking broadcast from ESPN just changed everything. Her critics were silenced by a bombshell announcement that exposed the truth about her unparalleled impact. Discover how one moment flipped the entire script and sent a clear warning shot to the league. Read the full story now!

In the high-stakes arena of professional basketball, where every rebound and crossover dribble can ignite a firestorm of debate, Angel…

The Quitter’s Dance: How Angel Reese’s Private Jet TikTok Exposed a Roster of Lies and a League in Crisis

In the unforgiving arena of professional sports, perception is reality. A grimace of pain, a look of determination, a moment…

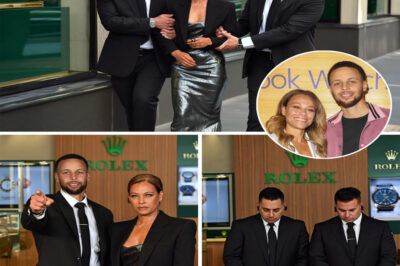

GLOBAL SHOCK: Stephen Curry’s Mom KICKED OUT of Luxury Rolex Store — What Steph Did Next Left the Entire World Stunned and Sparked a Fierce Debate on Power, Class, and Family!

Stephen Curry’s Mother Gets Kicked Out of a Luxury Rolex Store — What He Did SHOCKED the Whole World Stephen…

End of content

No more pages to load